I recently did an interview with the incredible Issy who runs Mixed Messages. You can read it here. It got me thinking, and I wanted to expand on it in a more personal piece over here.

I think that to understand my struggle with accepting my identity, it’s important to understand where I come from. This sounds like a skit, but I swear it’s not; I was raised and went to school in a Sussex town that has been dubbed the ‘UK’s strangest place’ by media outlets like Vice, BBC, The Telegraph, and all those tabloids. Why? Because the ley lines attract religious groups. In this small, sleepy, suburban town resides: the national headquarters for Scientology (Tom Cruise used to visit all the time), Opus Dei, the Rosicrucian Order, Jehovah Witness, Mormons (I lived right next to the Mormon temple), druids, pagans, wiccans, satanists, and more. Needless to say, it was a very white place. A quick Google tells me that the demographic is currently 92% white, with Bangladeshi, Indian and Pakistani making up the next bigger portion. I don’t think there was a single East Asian kid at my school.

Okay, so picture the above setting, then mix it together with early 00s culture, where casual racism is the highest form of humour: enter, Borat, Little Britain. This is what I was working with. I, like many half-Japanese people, am pretty white-passing. In any case, people can’t immediately place me. This means that growing up as a child, the ability to pretend that the East-Asian side of myself didn’t exist was relatively easy. I didn’t want to be different, I wanted to blend right in.

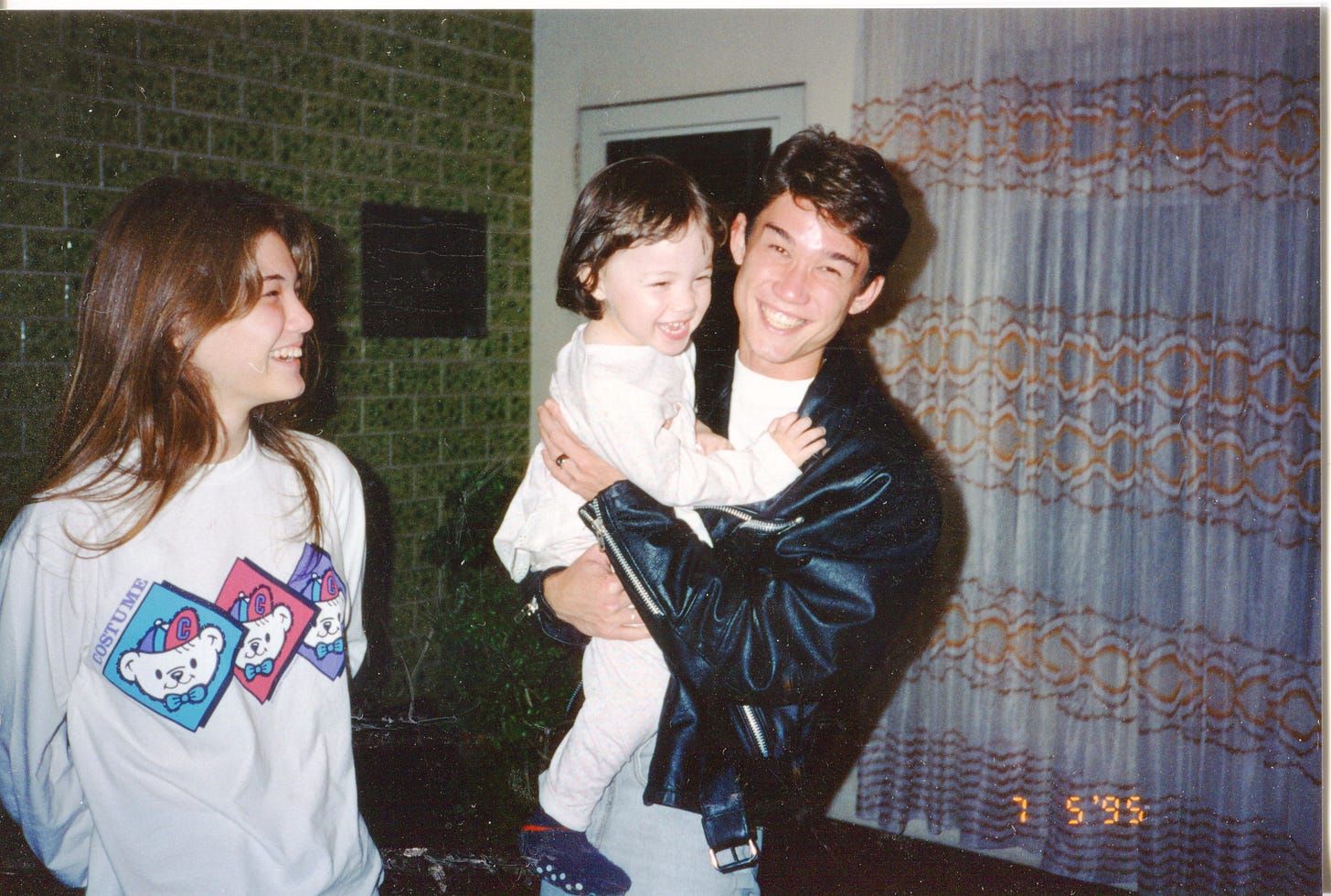

If kids saw my mother, I’d get teased because suddenly there was something ‘different’ about us. Something outside of the standard template for this weird little religious town. Nothing bad, I was never bullied, but nicknames were thrown about the playground - words that today in 2025 would be absolutely outrageous and completely inappropriate, but back in 2005 as we’ve discussed, seemed like peak comedy. I’m sure you can imagine the sort. These small instances made me feel even more like I wanted to just hide away. “I’m not asian, I’m Brazilian!” I’d say.

This was another issue - I was completely and totally confused. My father was Columbian-Scottish. His dad was a proud Scotsman, his mum a beautiful Columbian. My dad was born to them in Cali, Columbia, before moving to the UK as a child.

My mother was Nikkei Japanese - both her parents were Japanese but she was born and raised in Brazil. Due to Japan not allowing dual citizenship, she had only a Brazilian passport, and thus, referred to herself as Brazilian. You can imagine the confusion when kids saw my little asian mother who I referred to as Brazilian. I was totally confused, I had no contact with any of my family abroad, my parents did a pretty shoddy job of explaining my family history or culture or anything else to me, and all I knew was that I was different, and I didn’t want to be.

At home we spoke portuguese - my parents met in Rio, my dad was working there. And by ‘we’, I mean, my parents spoke portuguese, to which I would respond stubbornly in english, my accent thick and southern. The first time I said ‘init’, I think my dad nearly went into cardiac arrest. We ate Brazilian food, with the occasional Japanese supper on special occasions. I was never taught to use chopsticks. The one time I told my parents I was teased, (I think someone had called me a japseye), they were flabbergasted. The idea that I could be teased for being mixed had clearly never even crossed their minds. I was responded to with the ever-unhelpful, ‘they’re just jealous because you’re so beautiful!’ Yeah, right. Thanks, guys.

I had a boyfriend when I was fifteen. The innocent kind, where nothing really happens but you hang out and talk a lot. When he found out my middle name, I was mortified. “Kazumi?” He’d said. He pronounced it “kah-zoooooh-mee”. “I think that’s really cool,” he’d smiled. From then, he always called me Kazumi. My friends shortened it to Kaz, which I sort of hated, but tolerated. That boy, Rupert, was the first time someone made me feel cool for being different.

As I got older I continued to feign ignorance to any of my heritage. When winged liner came into fashion, I couldn’t line my eyes in the Ariana Grande way because of my epicanthal eye fold. Makeup caked onto my skin and was never quite the right colour for my skin tone. (This was 2010, we had about four shades to choose from, mostly called things like, ‘Porcelain’ or ‘Beige Sand’.) I started secretly Googling asian beauty hacks, feeling like the biggest outsider to ever walk the planet. And yes, I tried eyelid tape, and no, it didn’t work, because my eyes aren’t monolid, nor are they double lidded, but that strange inbetween, like all the rest of me. This was all going on while I was at university in Scotland, in a town where the population was 95.2% white.

After university, I worked in fashion marketing for many years. Imagine the whitest fashion brands you know. Those up-market ones where a t-shirt costs £50 for no reason. Yeah, those were the brands I was working for. I remember once asking whether we could get some asian faces on the social media, or some more diverse website models. The Creative Director looked at me as though I had asked if we could publish a picture of my morning shit on the homepage. I didn’t ask again.

Needless to say, I was desperate to get out of the fashion industry, and after many years of trying, I finally got a job where I was able to sidestep without taking a huge paycut in publishing. I was working as a marketing manager for one of the Big 5 houses! When I started, I couldn’t help but notice how different the industry was. For one, everybody was nice. And it was liberal. People had their pronouns in their emails. There were staff of all races, nationalities, and genders. In meetings there was always active conversation about how to diversify further, how to educate ourselves on racial matters, etc. There were committee groups for minorities, including neurodivergent and LGBTQ+ committees. Now, I’m not saying this job was paradise, it still had progress to make and problems to solve. But compared to what I had been exposed to thus far, it felt like I was in a melting pot utopia. Was it . . . okay to be different?!

The next few years my relationship with my identity developed in baby steps, as my curiosity grew. I joined the ESEA publishing network, and attended socials with so many East-Asian women. I didn’t even know this many east-asian women existed in London! One night at the pub, chatting to a colleague, I told her, “this sounds really weird but something about you . . . it reminds me of me?” She told me she was half-Japanese and my jaw fell to the ground. “ME TOO!” I practically screamed in her ear. She told me about a Whatsapp group called Hafus - A community group chat specifically for half-Japanese people in London. I could not believe my ears. Today, the group has 281 members with 9 subgroups, including one for art and culture. I felt like I was finally making strides in finding a place where I belonged, where my experience and identity confusion was less strange, less unique.

The biggest turning point for me was a book panel event I went to. It was a conversation on being mixed with Hanako Footman and Ela Lee. Hanako Footman is also half-Japanese, and she wrote Mongrel, an incredibly beautiful story which I recommend everyone read. I had loved it so much, hence going to the event. I listened to Hanako and Ela speak so eloquently on their identities (Ela is Turkish Korean), and on their own struggles in their industries - corporate law and acting. They seemed so confident and aware of their identities. They were open about their difficulties and also what they loved about being mixed. When I left the event, I turned to my husband, hand on my chest. “I have never felt so inspired in my life,” I said. He replied asking if we could go to McDonalds and asking what ‘prose’ meant.

From there, things quickly gained traction for me. The first thing I did was sign up for in-person Japanese classes, which I attended once a week in the evenings. (I also convinced my husband to sign up!) On top of the classes, the company who runs them would host loads of social events where I could meet so many other people interested in Japanese culture and language. This year, we even hosted three of our teachers at ours for a Burns Night supper, with my husband teaching them all the Scottish traditions and serving haggis, neeps and tatties, whilst they brought Japanese snacks and sake. It was such a fun night of blended cultures!

As well as Japanese classes, I tracked down some cousins on social media from my Japanese side and managed to get a hold of my family tree! This felt like a very emotional moment for me, as I had never managed to get much information out of my mother on this. Then, my husband and I travelled to Japan for the first time. I fell in love instantly. I couldn’t get enough of it; the cities, the countryside, the people, the food, the architecture, it was all just amazing. We’re returning later this year. It felt particularly special to visit Sendai, where my grandad was from, as a way to try to reconnect with myself. The people of Sendai were so kind and welcoming - even bringing gifts to me when I explained why I had come to this non-touristy city! I also loved being able to use some of my conversational Japanese that I’d learnt, proudly telling people, ‘watashi no igirisu to nihon no hafu jin desu!’ - I’m half Japanese, half British.

Of course, some things were still a struggle. For a start, their clothing stores are ‘one size fits all’. In a country where the average height is 5ft 2 and their weight hits at 52kg (I don’t think I’ve weighed that since I was about 13), it’s fair to say that I felt like a freakishly giant ogre. (I am 5ft6 and have an hourglass figure. We don’t need to discuss my weight xx). This obviously made me feel very western (my tattoos also didn’t help) but at the same time I was just so excited to be there, to be speaking with locals and reading train station signs in Japanese and gorging myself on onigiri that I didn’t really care.

Since returning from the trip, I’ve spoken on an ESEA panel for Women in Crime (one mild wobble beforehand where I hysterically confided to my husband, ‘I don’t know anything about writing OR being asian, I don’t know what I’m doing here!’ and attended various ESEA Author socials. I’ve also continued on with my Japanese studies and written a second novel, set in Japan, which will really explore being mixed race in Japan in more depth. I can’t say much more than that at the moment - but stay tuned!

So I guess that I’m on a continuous journey to understand myself, my identity, and what it means for me to be both British and Nikkei Japanese. But a huge part of embracing and reclaiming this long-neglected part of myself came when I chose to use my Japanese name as my Pen Name.

I had a horrifically embarrassing conversation with a friend who runs an ESEA committee. “I want to use the name Kazumi for my book, but I feel like an imposter?” I’d whispered to her. I’d just read Yellowface by R.F Kuang and was deeply worried that I wasn’t Japanese enough to claim the name, to sell myself as a Japanese author. She looked at me. “But . . . it’s your name? It’s on your passport and birth certificate, right?” she asked.

”Well, yeah.”

”Then you have more right than anybody else to use it,” she’d said.

I felt like a stupid idiot. At what point would I have been ‘Japanese enough’ to use my own Japanese name? Would I have to be fluent in the language? The owner of a passport? Live in Japan? Get some ribs removed so I can have a Japanese waistline?? I still cringe thinking about that conversation, that fear that I wasn’t entitled to my own name.

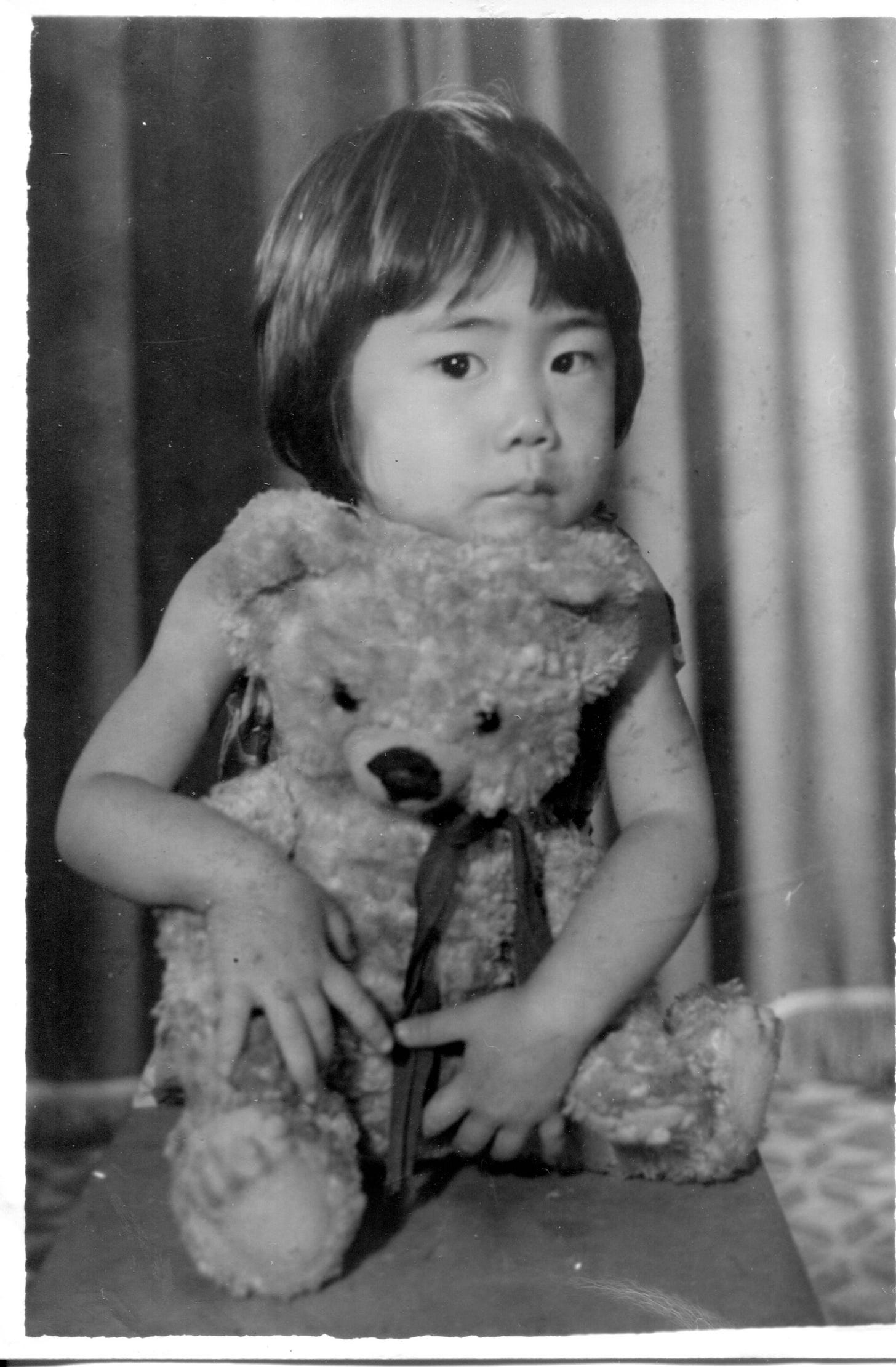

And so I want to take a moment to reflect on the name as well, and what it means to reclaim it. My grandad was called Minoru. They wanted to carry the ‘mi’ ideogram through the children, my mother’s name is Mieko (which translates into ‘daughter of minoru’!). Her siblings are Mihoko, Hiromi and Yoshimi.

When me and my sister were born, my mother wanted to carry this on through us, and gave us our Japanese names. I got Kazumi, my sister got Kiomi. So although it’s just a name, it’s actually more than that. It’s a link through my entire family - most of whom I’ve never even met before, and tells a story in itself. My grandad met my grandma at a time where in Brazil, Japanese arranged marriages were normal. But my grandad and grandma weren’t an arranged married - they fell in love exchanging books. This feels particularly poignant to me, as though I have another piece of them within me. When we were last in Japan my husband got me a handmade hanko stamp with Kazumi on it. This felt like the final step in reclaiming my name, taking it back, and making it mine. I may not be fully Japanese, but I’m not fully white, either. And I think being Callie Kazumi illustrates this just perfectly.

Love, C x

Here from the hāfu group chat! Thank you for sharing — what a blend of cultures and experiences to bring you to where you are today. ♥️

Thanks for directing me to this. Makes much more sense now. Much love! ❤️❤️❤️Dx